Tom Britton, Cofounder of Syndicateroom, is a regular speaker and mentor on EnterpriseTECH and EnterpriseTECH STAR. His easy-access and lively discussions are pitched perfectly for the new-to-entrepreneurship students attending our programmes. Tom shares thoughts on product-market fit for our student audience in this blog.

“Product market fit (PMF) is the holy grail for any start-up, but few founders fully understand what it is and even fewer manage to achieve it. Below I’ll quickly cover some thoughts on what it is, give some tools and suggestions that can help you find it, and share a very short case study that demonstrates why achieving it isn’t the promised land many make it out to be.

“When growth is no longer your problem, keeping up with demand is” – Marc Andreesen (a16z)

What is product-market fit?

“Product/market fit is when people sell for you” – Josh Porter (HubSpot)

Search Google, and you’ll find hundreds of millions of hits for product market fit, and they all have a slightly different take. Some focus on hard metrics, while others have a more qualitative view. My personal opinion is somewhat of a mix though slightly leaning toward the metrics side.

While I like both Josh Porter and Marc Andreseen’s views, they are both tied more to the marketing than the product (and can be considered as much) signs of hype or underpricing as they can of true product market fit. Think of any of the latest fads that generated a quick cult-like audience and then disappeared seemingly overnight. Do any of you remember Juicero? My point exactly. They raised over $100m to be the Nespresso of smoothies and failed spectacularly after a massive marketing effort and a small amount of hype.

Similarly, overlooking a product’s cost component means neglecting the ability to exist beyond a short period of time. Selling something for far less than what it costs to make can generate hype and cause a spike in demand, but it is not sustainable. Therefore, product-market fit must incorporate an element of cost such that it is only truly considered to have been achieved when the cost of selling a product is less than the cost of producing it.

So when I think about product-market fit, I think of a product where customers willingly – and repeatedly – pay more for it than it costs the business to make, market, and service. That said, I think word of mouth and demand-based metrics, as well as others if used correctly, can help indicate when you are on the path to product-market fit.

Achieving product market fit

The first step to achieving product-market fit is understanding what the market needs. In my experience, there is no better way of doing this than by using the ‘jobs to be done’ framework developed by Clayton Christensen and his team.

“People do not want a quarter-inch drill; they want a quarter-inch hole.” – Theodore Levitt.

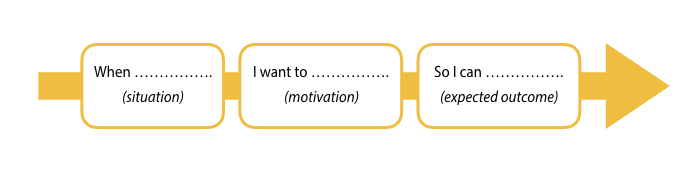

At the core of the JTBD framework is the customer need and the context for that need. To address ‘the need’ (not a symptom of the need), founders need to understand their customers, goals and environment instead of just listening to what they say. Spending time with customers in their everyday environment where their need has developed creates a better understanding of what the product should be. The simplified output of the JTBD puts it into this perspective:

Harking back to Henry Ford, if he had just listened to customers instead of digging deeper, he might have spent his life trying to figure out how to get horses to run faster instead of building automobiles. Once the JTBD are clear, it’s time to prototype, fail, learn and iterate.

Prototyping doesn’t necessarily require building a version of the final product or service. Instead, using paper prototyping or simulations can help customers get a sense of what you are trying to achieve for them. This way, you can learn and iterate the product or service further without spending time (or capital) trying to produce the actual product too early in your journey.

Your first prototypes will be ugly. If you are happy with them, you’ve spent too much time devising them. You should include the essential features your customers require and one or two differentiators. Don’t think you must have all of the features of a competitor, just the ones your customers identified explicitly as a need.

When you’ve got enough data and versions in the bag to be confident your customers can get use from the product or feature, you can move to developing a proper prototype and going back to new user testing.

A few words on this testing and getting feedback:

- Avoid leading questions by keeping them open-ended and yes/no as much as possible.

- The answer to any question of “do you want…” or “are you concerned with…” will always be yes. So avoid these types of questions.

- Unless the response is an enthusiastic “yes we love this”, assume the user is being polite.

- If their response is slightly negative, their real feeling is much worse.

- Don’t let users suggest anything without explaining why they want/need that. The reason they want/need it is far more helpful to understand than the what.

- Nobody wants to look dumb, so they’ll never directly say your product/service is too complicated. Be on alert for difficulties understanding or navigating it.

- Last note on achieving product-market fit, the moment you act as if you’ve reached it is also the moment you lose it. As you’ll see below with Kodak, the market is constantly evolving, and your product/service must evolve to meet the new needs.

Kodak, a perfect picture that didn’t age well

Too often, companies define themselves by their product which can lead to serious problems. This was the case for the Kodak corporation, which had achieved one of the most prolonged periods of product-market fit before losing it all.

“To maintain product-market fit, always act as if you don’t quite have it.” – Tom Britton, SyndicateRoom.

Throughout the 70s and 80s, Kodak dominated the market for film and the tools and chemicals needed to process it. Kodak had always viewed itself as a “film” business, so this was music to executives’ ears who drove the company to a peak valuation of $31 billion. However, being a “film” company and not a “memory capture business” (for example) had its limitations, particularly on the company’s vision. In 1975, an engineer at Kodak developed the world’s first digital camera and the first megapixel camera shortly after.

Had Kodak been a “memory capture business”, this would have been a terribly exciting development. However, because it was a “film” business, the engineer was reprimanded and asked to keep the development quiet instead of being praised since the new technology could damage the company’s film sales.

Twenty years later, the film business peaked and was on the way out. Had Kodak used a JTBD lens, they could have seen the advantages of the new technology and the long-term prospects. But instead, they focused on maintaining existing revenue streams and ultimately lost over 95% of the market.

Today Kodak still exists, though it’s been through bankruptcy and was bailed out. The business now focuses on high-speed digital imaging and printing, using and licensing the patents it developed over its 130-year history. While not the behemoth it once was, Kodak is listed on the stock exchange with a market cap of around $400m.

While the film JTBD has declined to near extinction, the memory capture business has continued to evolve, with social media sites the repositories of memories captured on mobile phones. Had Kodak viewed itself in this light, we might be surfing our memories on a Kodak-built network or capturing them using a Kodak phone.

What’s next?

Speak to your customers and home in on the tiny things that excite or annoy them. Then, use the JTBD framework to understand the underlying need and build from there. If you’d like more on JTBD, Clayton Christensen’s ‘Competing with Luck’ is a good place to start.

Follow Tom Britton on Twitter @tombritton. He is happy to chat through this or talk about raising capital. If you are aiming to raise or are raising in the UK, Tom suggests looking at SEIS, EIS.

Martin

Extremely useful article