Ahead of our Enterprise Tuesday in November entitled ‘What’s your story?’, I have been thinking about stories, how they have influenced my working life and what they can teach us about today’s world we find ourselves in.

I’m writing this on Sunday 4 October 2020, 90 years to the day that saw the final act in a story that has fascinated me for over twenty years, the British Airships programme of the 1920s. So much so, that I’ve been trying to turn it into a film for the last decade. There’s a whole separate blog on that process, but for now, let me focus on an aspect of that story that intrigues me and which I don’t mention to Hollywood when I’m pitching it. When I talk to the studios, it’s a disaster movie, pure and simple. But what is really fascinating I think is the story of state vs private enterprise – a story that resonates all the more because of events this year. It’s a truism that entrepreneurial companies have coped better with this crisis than big government – the airships programme was an early demonstration of that.

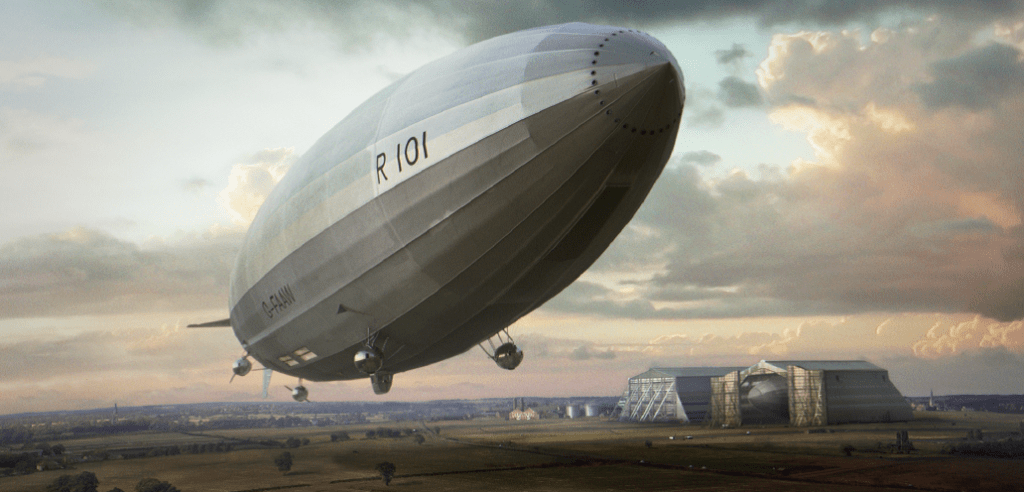

After the First World War, Britain saw an opportunity to become world leaders in the only viable means of mass transportation in the air, the rigid hulled airships made famous by Zeppelin. The German economy was in ruins and here was a real opportunity to unite the Empire by cutting down the travel times between the far-flung colonies. But to its horror, the newly formed Labour Government of 1923 found that the only private company who could design airships was Vickers, the armaments company which to them, was steeped in the blood of the working man shed in the trenches. So they came to a classic British fudge. Two airships would be built – one designed by the government at Cardington, outside Bedford – and one by Vickers in a draughty shed in Yorkshire. The press called them the Capitalist and the Socialist Airships. The capitalists, working to a fixed price contract, were led by Barnes Wallis, the engineering genius who went on to design the Wellington bomber and the Dambusters bouncing bomb. Their struggle to get into the air was brilliantly documented by his chief assistant, the writer Nevil Shute as, away from the limelight, their ship, R100, met the specs required of it, flew to Canada and returned triumphantly. Meanwhile, the government airship, R101, designed by committee, lurched from problem to problem until, pushed by an impatient Air Minister, Lord Thomson, took off on 4 October bound for India with Thomson on board, only to crash later that night over France, killing him and 48 of the 54 people on board.

And here’s the really interesting thing in relation to where we are today with handling CV-19. When R101 took off on its maiden voyage 90 years ago today, its designers, all decent men, knew it was a seriously flawed craft. But the government, so keen to take the lead, had issued so many upbeat press releases and trumpeted its many ‘world beating’ innovations so loudly that no one felt able to stand up in public and say, this ship is too dangerous to fly. The lack of public debate was fatal and they paid for that reticence with their lives. Had they talked more to the private enterprise team on R100 they would have shared common difficulties and found solutions. Had they been more open about the problems they wouldn’t have trapped themselves into a cage of their own making.

Colin Burrows, Founder of Special Treats Production, will share insights and expertise on Tuesday 24 November. Book your place >

Leave a Reply